Sunday, November 11, 2007

Word and Helen Adams

In this lecture that I've been listening to, she reads from Through the Looking Glass and talks about music of poetry. And then she just sings in a nice scottish-y way.

The other best part of the movie was Allan Ginsburg. He's like a tweedy economic professor doing karaoke.

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Read Robert Hass

My Mystical Turn

I was reading the diaries of the young Simone de Beauvoire who, I discovered, was quite in love with Merleau-Ponty (the subject of my erstwhile dissertation). She claims– much to my surprise, informed by his lush writing on embodiment – that he is naïve, Catholic and obsessed with abstract metaphysics. (He was only twenty or twenty-five at the time, and it is my thought that he was in love with her too and stylized himself in response to her rejection) She said of speaking to him, “I say, ‘skepticism.’ He says, ‘laziness.’ My skepticism has its excuses. Yes, but one must not need to be excused.” (July, 1927)

So… I have been skeptical. But one must not need excuses. This is just such ridiculously good poetry! Kabir … “ the musk is in the deer, but it seeks it not within itself: it wanders in quest of grass.” Rumi… “close the language-door and open the love window; the moon cannot come in the door, the moon must come in the window.” And “loves comes with a knife, not some shy question … The sun rises, but which way does night go? I have no more words. Let the / soul speak with the silent articulation of the face.” READ MORE

I have also been reading Hopkins. And I wrote about him. But I read him in the context of these fellows … A trope that persists through all of theses mystics is madness and intoxication by desire. This sounds so universal & vague as to be trite … but Rumi is not trite. Bertrand Russell – analytic of analytics – confessed that he had two great fears: loneliness and madness. The worse of it was, the one caused the other: the less mad he was, the more rational he was … and thus the more lonely. The less lonely he was , the more intimate he was… the more mad he was. I love this… and mostly because it’s crotchety old Russell who said it! (though, he did have 4 wives, the last when he was nearly 80 yr old!)

So, I have lots of new work this week. I don’t know if it’s all good or at all good, but I have been writing tons.

All these “I” pronouns in my work make me nervous…. I am worried that I wouldn’t like my work if I picked it up. What is the work about except me?? I wish I had the same poem(s) without an I. I worry that I’ve let this “I” slip in at certain encouragement but without my own approval… on the other hand, it’s been so freeing. Much like reading the mystics. It feels like more aural/oral poetry than poetry on the page. I’m just writing the way I think when I walk.

I had an interesting conversation the other day with Brendan Kennelly. He’s a pretty darn well known Irish poet who happens to have a chair at our strongly Irish Catholic School. He’s rather old and his only job is just to stay around campus and write. My adviser - an Irish philosopher—and I were having coffee last week and we ran into Kennelly and I was introduced. Later in the week, I was walking around campus and crossed his path and he said, “Isn’t it a lovely day?” And I said, “Yes, it ‘tis.” And then I re-introduced myself and we had a nice chat. Then he “spoke” me a poem... he insists that he only speaks poems, he doesn’t write them. The poem was about a loaf of bread he remembers watching his mother make. The poem was told from the point of view of the bread, and it began, “Someone cut my head off in a field…” And ended with the bread being torn and consumed by the mother. Wow. (wow with an explicative and raised eyebrows!) He just recited this to me sitting on a bench on campus. He asked me about my work … and my work is … on the computer? I couldn’t recite anything! (and summarizing poetry is worse than not writing it) So I changed the subject.

This past week he gave a public address... in which he spoke his own poems and the work of maybe 5 or 10 other authors from the last 50 years of Irish poetry. All from memory, not one note for an hour. He is a rhapsode in the strongest meaning of the term.

So for the past week, I’ve been trying to memorize little things. Some Rumi. Some of my own. So that, at the least, if I run into Mr. Kennelly again, I can recite something for him. The summer, before the WW retreat, I memorized the first 15 or so sections of George Oppen’s “Of Being Numerous.” That was a great exercise. It’s really hard for me… I am such a visual person. When I used to play the violin, even though I supposedly learned through the Suzuki method, I actually just memorized the look of the sheet music and watched it. I worry that I don’t have enough music to be a poet … shouldn’t I think like that?

I do write often while I walk. Mr. Kennelly and I talked about that too… about Coleridge and Wordsworth and then, locally, Emerson and Thoreau. He said Coleridge and Wordsworth walked twenty or thirty miles a day. I think actually some of my better poems are one that I write that way : these peripatetic poems end up only being as long as what I can manage to memorize on my walk and write down upon return. My walks are limited by modernity and my busy schedule and the poems are thus limited by those factors plus my weak aural memory. But … maybe those are good strictures to hold to. Could Oppen himself ever have memorized all of “Of Being Numerous”? Could Shakespeare recite all of Hamlet? Maybe he could have, actually…

So.. to summarize ;) I have been, of late, concerned with the aurality/orality of poetry and poetry as unconstrained, mystical speculation. This is quite a far cry from my concerns a year ago, or even six months ago

Monday, October 15, 2007

Ein Drohnen, Paul Celan

die Wahrheit selbst

unter die Menschen

getreten,

mitten ins

Metapherngestoerber.

P. Celan

Tuesday, October 02, 2007

John Koethe

Was nothing special and I wouldn’t want it back,

Yet sometimes when I think about the years to come

I see almost as many as the ones since then.

I feel a vague and incoherent fear, a fear

Of waking from time’s dream into an even stranger place,

As different from today as now is from nineteen,

Without a sense of where I am or where I’d been before –

Which is always here, in my imagination.”

- John Koethe, from “The Maquiladoras”

Sunday, September 16, 2007

Paul Celan and the Museum of Bad Art

We went to the Museum of Bad Art this weekend in Dedham, MA. A really fun trip … I recommend it, though you should be cognizant of the fact that you are going to have to drive a good 45 minutes at the least from somewhere to see ... well, BAD art. But the commentaries are what make it .

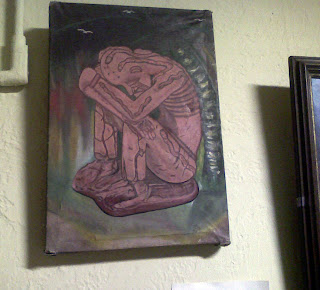

So, it was a *fun* trip and you shouldn’t think I was moping about this the museum. But, while I was looking at some of the bad art, namely this one,

I was thinking about what makes people make precisely this kind of bad art. I mean ... the poor guy obviously just wanted to pain Loneliness. What first year art student doesn't try to paint Loneliness, in some way or another? (Or another Bad Art favorite topic such as People Making Love, or just Love or Passion.) Now, I'm not saying they necessarily set out to paint the noun with the capital letter... but they end up with an image like this, whether in sculpture, painting, or photography. All this abstract art and all this talk about it... and really all that 98% of us want to painting are images of people, happy or sad. And.... in a way, there's nothing really wrong with the topic they've picked; the execution alone sometime does qualify them as bad art . Discussing the execution doesn't explain whether or not the impulse toward these images itself is misplaced.

I was thinking about what makes people make precisely this kind of bad art. I mean ... the poor guy obviously just wanted to pain Loneliness. What first year art student doesn't try to paint Loneliness, in some way or another? (Or another Bad Art favorite topic such as People Making Love, or just Love or Passion.) Now, I'm not saying they necessarily set out to paint the noun with the capital letter... but they end up with an image like this, whether in sculpture, painting, or photography. All this abstract art and all this talk about it... and really all that 98% of us want to painting are images of people, happy or sad. And.... in a way, there's nothing really wrong with the topic they've picked; the execution alone sometime does qualify them as bad art . Discussing the execution doesn't explain whether or not the impulse toward these images itself is misplaced.READ MORE

I heard an interesting lecture on cliche this summer by poet/classicist Brooks Haxton. Haxton argued essentially that cliches work... that half of Shakespeare's sonnets are cliches. He was being polemical, but his point was that audiences enjoy cliches, or at least the content of them. For one, we like repetition, we like familiar territory. For another, the things of cliches are the things, for the most part, that matter ... life, death, love, loneliness, joy, heartbreak, etc. But it isn't just the content that we want to hear repeated ... we like the form to be similar too. A truly great poem manages to give you all that with some subtle permutation so that you hardly realize it was familiar until you feel the pleasure afterward.

Which brings me to Paul Celan. I have been reading Celan this week, for the first time seriously. I've read single poems and read about him many times -- it's hard to be an continental philosophy program and avoid the name -- but I've never delved into him. I decided it was time to tackle him. I bought two translations with German and English text beside eachother and settled in this morning.

Well, needless to say, this was quite a way to being a Sunday. I was overwhelmed. I tried reading the German out-loud, then reading the English silently and going back to the German so I could fit sound with sense. Many of the images in the early poems particularly, came from this 'cliche' set of topics and even imagery; he speaks of water and flowers and circles and blood and milk ... and of course death. But the presentation is so peculiar that these most familiar images are strange and disconcerting; "poplar" and "poppy" become morbid and threatening instead of pastoral and cheerful.

Tom Sleigh once said to me, “John Ashberry is the greatest living poet. You should read him. But you should never try to write like him.” I would say something similar about Celan, except that he would be German and dead. He’s too good; he’s archetypical. You can read this for years and acquire a taste for its strangeness. But you should never, ever try to write like Celan.

At the same time ... Celan writes about what all poets want to write about. How can we not take him as a mentor, as a guide? How can him be great if he is not a model to follow? Many Kantian phrases about genius and beauty come to mind, but I am dismissing them because they only circumscribe the question rather than answer it... novelty intrigues but repetition pleases. A rose is a rose is a rose. And it is pretty...

Sunday, September 09, 2007

Prose of the World

-Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Prose of the World

Anglophilia

God, I really wish I could live here! I don't say that about many places ... in fact, I can't really remember saying about anywhere. I mean, Tuscany is beautiful, Paris is exciting, Germany is cozy and I've contemplated spending time in all those places. But I can actually imagine moving to the UK and being an ex-pat permanently.

It's partly the language-thing (easier to imagine being an ex-pat when ordering dinner isnt' stressful), but it's really more than that.... I really have mythologized the place until it's sort of already part of my psyche, like a place you grow up in, or miss, I feel a bit of Seinsucht and all that. I've only actually been to London before and I know this is a bit precipitous -- it only being a four day stay and all! -- but I really don't think I've reacted this way to a place before. (I'm going to apply to another conference here, hoping to come back!)

It's as if the England that I imagined and researched around those stories became the setting for *all* my dream life, whether or not it related to the myth. Perhaps other people have another place that functions this way -- maybe Italy, maybe a summer holiday place, a particular garden near your house, maybe Iceland, I don't know -- and I can think of others for myself, but none as strong as England. England was my archetype of mythological space.

I'm not saying I find England to actually meet my idealized version of it -- although I did take a mostly romantically perfect walk in the countryside today! -- but rather, whether or not its current conditions meet my expectations, it already *is* my dream world. It's particularly the physical landscape itself ... the shape of the hills, the proportions and layout of the villages and countryside. They share something with the hills of Southern Ohio where I was raised, but with a bit of cultivation, compartmentalization. Certainly this has been amplified as fantasy in *every* American's imagination by Romantic reproductions, be they paintings or gardens by Fredrick Law Olmstead, but because of my particular (by no means singular) attachment to those King Arthur stories, the exponent of archetype has been raised by another power.

Well... I'm going to go back to sighing out my window to see if Lancelot is on his way while I get over my jet lag.

Thursday, August 09, 2007

Carl Phillips, "Sea Glass"

can't help that it looks like one, any more than

it can avoid not being able to stay."

- Carl Phillips, from "Sea Glass"

Wednesday, August 08, 2007

Why isn't Poetry a Graphic Art?

I think poet’s are a bit afraid to talk about that… there would be too much to deal with . But I think we need to acknowledge that the unwritten rules of the game are that you write with Times New Roman at twelve points; it’s like not acknowledging in the sixteenth century that iambic pentameter was standard. I’m certainly not against having standards, any more than I’m against an other formal frameworks. The Times New Roman standard gives a certain graphic grammar to bump up against. At some point, someone had to come to the full realization that iambic pentameter was the standard and then he could take full advantage of the possibility of diverging from it.

But can the same thing happen with the graphic presentation of the poem on the page? Historically, we’ve moved from poetry as completely orally/aurally transmitted to poetry as an art whose printed component factors significantly in its assessment. But I do not think that we’ve fully made the paradigm shift. Perhaps this is only now possibly as typographic software allows the poet to experiment in private (as poets like to do) with the potential formal variations. I imagine that there are poets – Olga Broumas comes to mind – that poetry is primarily an oral art and thus the visual and physical dimensions of its presentation will always remain secondary. I would argue that it’s already become a printed art; as much as the news went from being the material of the town crier to the material of the printed page to the stuff on the digital screen, poetry can cross media. Poetry is, of course, one of the older arts, and conservative in its way; perhaps it’s just not ready to make the changes. Perhaps… Olga’s right and it won’t ever be on the page any more than Beethovan or Miles Davis is in the sheet music. But couldn’t graphic presentation be just a better tool to help the reader hear more clearly in her mind’s ear?

Saturday, August 04, 2007

"Open the Door..." Emily Dickinson

" ' Open the Door, open the Door, they are waiting for me,' was Gilbert's sweet command in delirium. Who were waiting for him, all we possess we would give to know -- Anguish at last opened it, and he ran to the little Grave at his Grandparents' feet -- All this and more, though is there more? More than Love and Death? Then tell me is name!"

When Dickinson wrote poems, she wrote them on regular paper and collected stacks of these papers. She never published anything publicly but after a few years she would polish her poems for her self. She'd recopy them onto nice stationary, stack up a few sheets, punch holes in the edges and bind them together with string (these groupings are now called fascicles). She destroyed all the earlier drafts of the poems and put the fascicles on her shelf. Her handwriting wasn't very good; it was pretty but hard to read, a bit long and scrawly. It seems she really never intended anyone to read poems.

I don't think publication or popularity necessarily reflects the quality of a poem or poet, but I can't imagine what writing is if publication -- in the simple sense of making public -- is not the aim. What is this thing that Dickinson was doing if it was completely private? R Kearney always says that literature is someone says something to someone... and hermeneutics deals with each of those "some--"s. But to whom was Dickinson speaking except for a couple friends in letters? To herself? To God? When George Herbert writes confessional poems to God, he was so religious in a strict Christian sense that he actually believed he was speaking to an invisible being who could hear the words, whether or however this being responded.

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Antipodes

From the OED:

antipodes, n. pl.

1. Those who dwell directly opposite to each other on the globe, so that the soles of their feet are as it were planted against each other; esp. those who occupy this position in regard to us. Obs.

2. fig. Those who in any way resemble the dwellers on the opposite side of the globe. Obs.

3. Places on the surfaces of the earth directly opposite to each other, or the place which is directly opposite to another; esp. the region directly opposite to our own.

4. a. transf. The exact opposite of a person or thing. (In this sense the sing. antipode is still used.)

The antipodes seem to be our opposites, but not malicious; they're not our evil counterpart, just our significant other. A bit like today's 'dark matter.' (Antipodes sounds about as scientific as 'dark matter' does any way... ) Maybe these antipodes are just our shadows.

Saturday, July 21, 2007

Asheville Shindig

Robert Pinksky "Keyboard"

The one who touches the keys a solitude

Inside his music; shout and he may not turn:

Image of the soul that thinks to turn from the world."

- Robert Pinksky from "Keyboard"

Thursday, July 19, 2007

Lyric

- William Meridith.

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

Ontology and Address...I, You, Ich, Du, Sie, Vous, Tu...

We speak often of the problem of the “I” in lyric poetry, but what of the “You”? Literary critics struggle with whether to assume that the “I” who speaks is the poet or a character or a narrator, but perhaps the first question ought to be, “to whom is this ‘I’ speaking?” To start with the “I” rather than the “you” implies a certain ethical and ontological stance that may not be appropriate to all lyric nor even to all speech.

George Herbert’s devotional poems, such as "Jordan (1)" would be incomprehensible without considering the “You” that the poems address. This “you” is generally either God or a fellow Christian (or both simultaneously), or a potential convert or wayward Christian. This you, especially when it indicates God, is a powerful force. The poem is not a circle radiating from a central “I” but an ellipse, defined by its two poles.

While I do not intend to address God in my poems, I do often use direct address and dialogue. I am struggling with the role of the “I” in poems – whether I want one to write with this pronoun at all, or if so, with what relation to have to the pronoun -- but I had not considered the opposing “you.” This, perhaps, says more about my character than that of anyone’s poems.

But why do we assume the I is equivalent to the poet? I'd be open to the possibility that other people consider the "you" first, but a number of grad and undergrad literature courses suggest that most people make that fatal intentional fallacy. Does our tendency to make the intentional fallacy suggest something about our original relationship to the world? Or, perhaps, conversely, we cannot help but feel addressed by the poem... implicitly called to by an other behind the page.

Herbert's poems do not call directly the reader: they speak to God. The reader, for the most part, simply listens in on conversations between the poet and God. “

Because the poem actually puts the question to God, this is not idle speculation; as a Christian minister, Herbert could expect an answer of sorts. The answer might not come in sonnet reply, but as addressed to God, his poem takes on the power of prayer. This element of “craft” is performative: Herbert performs prayer in poetry. His craft choices addresses the problem of craft: should poetry craftily generate more false images of “enchanted groves” and “purling streams” or should it speak directly (to God) and avoid artifice?

Of course, the poem itself appears within a sturdy form: iambic pentameter with alternating end rhyme. Apparently, this aspect of craft is appropriate or necessary for communicating even with God. When a poet writes in images, it causes all to “be vail’d” and “he that reades, divines, catching the sense at two removes.” God, of course, created the original world; poem that addresses God in images would be periphrastic. Herbert even begs that he not be punished “with losse of rime” because he would use his rhymes to say “My God, My King.” In “

Identifying the addressee of the poem as God implicitly suggests that the speaker of the poem is the poet. If this poem truly performs prayer, then it must be prayed by a living soul, not a fictional or artificial narrator. Confession not only celebrates God, but confesses one’s own sins; to create a ‘narrator’ dissociable from the poet would prevent the poem from fulfilling this second function. If the poem addressed someone else – say, a mother or a lover – we could possible envision a scenario in which the narrator has an identity distinct from the poet. For example, as Linda Gregerson points out in “Rhetorical Contract in the Erotic Poem,” the famous Marvell poem “To His Coy Mistress” appears to directly address the lady beloved, but in fact the title offsets the addresser and addressee as his coy mistress. The title casts the poem in an ironic light; someone is saying this to his lover, but it isn’t necessarily the poet. To do the same to an address to God, would be to mock the entire framework of the confessional poem; the poem would no longer be confessional nor could it perform the act of prayer. We must assume sincerity in address in the Herbert poem; the craft element must be taken as intentional in order for the poem to have its intended effect.

Geroge Herbert - "Jordan (1)"

Who says that fictions onely and false hair

Become a verse? Is there in truth no beautie?

Is all good structure in a winding stair?

May no lines passes, except they do their dutie

Not to a true, but painted chair?

Is it no verse, except enchanted groves

And sudden arbours shadow course-spunne lines?

Must purling streams refresh a lovers loves?

Must all be vail’d, while he that reades, divines,

Catching the sense at two removes?

Shepherds are honest people; let them sing:

Riddle who list, for me, and pull for Prime:

I envie no mans nightingale or spring:

Nor let them punish me with losse of rime,

Who plainly say, My God, My King

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Randal Jarell from "The Lost World"

Talk with the word, in which it tells me what I know

And I tell it, "I know--" how strange that I

Know nothing, and yet it tells me what I know! --

I appreciate the animals, who stand by

Purring. Or else they sit and pant. It's so --

So agreeable. If only people purred and panted!"

- Randal Jarell, from "The Lost World"

Addendum to "Do Poems Have Any Ideas"

Do Poems have Any Ideas?

These ideas -- these forms of life -- appear on the page from letters that make words (that conjure connotations) that make lines that also continue into or contain sentences (that have rhythm and music that set a mood) that make stanzas that generate images in my mind and the mind of other readers. The stanzas also produce characters and voices that may speak to me discursively -- i.e. communicate 'abstract' ideas -- but these are precisely voices and characters that speak in my mind, not mere abstraction. But through all this... just as, walking through an Ernesto Netto sculpture ... I received ideas. The art comes, Oppen says, when one feels the one thread ("One cannot come to feel he holds a thousand threads in his hand... this is the level of art") and that one thread is the form of many things, many aspects, many experiences.

I do not care for art that does not take its ideas seriously. Feeling ... well. You will feel something; but you can feel something looking at a bleeding rabbit or by putting your hand near a flame. Art builds a home for feeling to live in. Artifice is not the opposite of sentimentality; it is its human form.

No doubt this sounds like the ranting of a philosopher feeling unimportant or else someone who hasn't mastered her 'craft.' Certainly it is both. But I think some frustration is justified... and not just in regards to the program I am in now. It's quite a problem for artists in general, of many disciplines deal. But to take an example from this week, the well-known poet leading a discussion of Oppen's work wanted to talk about the tropes of "fate" and "being numerous"

in his poems but without discussing the ideas. She merely located the recurring themes in the text, marveled at them, made a few of her own comments about fate and was content to say that Oppen had read Heidegger. She resisted any discussion of what Oppen might really have said about singularity, perception, or death; she just wanted to discuss their presentation. I'm not advocating for literary analysis of the allusions to Heidegger or Husserl (both of which appear all through the Oppen) exciting as that might be ... but a discussion of Oppen's work that only describes imagery and syntax is like a description of a meal in terms of color and arrangement with nothing to say about taste and digestion!

Oppen's work -- like Goethe or Dickenson's or Carson's -- deserves to be respected precisely for its ability to communicate the ideas. Part of learning the craft of poetry must be learning how to communicate ideas therein ... which requires figuring out what a poet's ideas are and how they appear out of the syntax and voices ( and ought also, in my opinion, to include learning to think more carefully about these ideas, but perhaps that's leaning too far to the philosophical right or left.) To ignore that presentation in favor of asking either merely what the poem made you see or worse, made you feel is to oppose artifice not only to sentiment but to comprehension. Artifice allows sentiment to arise as it allows comprehension to arise. The great art of Bishop in "Crusoe in England" say, gives us the pain of Friday and Crusoe; it also gives us ideas about human finitude and friendship and intersubjectivity. That sounds like a shallow summary of Bishop and it is! Bishop's ideas are as complex as her presentation and I can't summarize them... they are poetic ideas, presented in poem. But that they appear as poetry does not prevent their ideality.

--

"One must not come to feel that he has a thousand threads in his hands,

He must somehow see the one thing;

This is the level of art

There are other levels

But there is no other level of art"

- George Oppen. "Of Being Numerous," 1968.

Monday, July 09, 2007

View from poetry boot camp

Today I heard a fabulous talk on James Wright's Two Citizens. Apparently the book was panned because it diverged from his earlier imagistic work and turned to focus on colloquial language. Alan Williamson did a close reading of "Ohio Valley Swains" that opens "The grandaddy longlegs did twilight / And light" moves from lyric to close with "and if I ever see you again, so help me in the sight of God, / I'll kill you." I think it's a perfect narrative poem. Williamson, citing Kristeva, described Wright's technique as "pre-position" in which he inserts certain phrases or allusions earlier into the poetic sequence than the narrative sequence. In Kristeva's view, this indicates the "pleasure principle" (showing what's important to *me*) winning out over the "reality principle" (accurately giving an account for the other/reader). Now, in either poems or conversation, I am thinking about whether the pleasure or reality principle is winning (for me or for my interlocutor).

In another talk on "Daring, Drama, and Melodrama" given by Baker, he cited a poem by Linda Gregerson that really blew me away with its epic, almost cosmic ennui. Gregerson is someone I would like to read more closely. He also read an amazing poem by Auden that manages to avoid sentimentality while rhyming and concluding with the following lines :

"Much can be said for social savoir-fare,

But to rejoice when no one else is there

Is even harder than it is to weep;

No one is watching, but you have to leap.

A solitude ten thousand fathoms deep

Sustains the bed on which we lie, my dear;

Although I love you, you will have to leap;

Our dream of safety has to disappear."

Mythos vs. Logos

- Poets are performers and persnickety. Philosophers are mostly ex-nerds or averages joes (mostly joes, also mind you, not janes where as poetry departments are heavy on the ladies) who like to use dinner to argue. Poets either don't speak much at all or are extrordinarily cool and prefer to use dinner to drink and to gossip rather than pontificate.

- Poets think they are in some way "ordinary people"... they're writing about what's really happening, what's really out there, for what people really care; philosophers argue about why what they do is applicable or underpins what's going on "out there" but rarely simply accept that they are doing what "regular people" are doing

-Poets and writers really don't care about argument! They occasionally think they do of course, but it's nothing like philosophy. Seth Bernadette can find all the argument in the action he wants, but something really happened when mythos and logos diverged...

- Poets mine the current events, encylcopedias, and art exhibits for images and tropes to link in intuitive associations where philosophers look for evidence, trends, and historically contextualized trivia that they can place neatly in a stable niches of a well-constructed historical or analytical account.

- Poets read other poets and allude to philosophers to make things sound cosmically significant. Philosophers read other philosophers and allude to poets to make things sound humanly significant.

Sunday, July 08, 2007

Serious, seriously

I've realized what a philosopher I've become and also how much I miss writing. I don't talk the talk here; at a philosophy conference / conversation, I know enough to know what I ought to know (but usually don't) and thus when to keep quiet or when it's reasonable to ask a question ... here, people are mentioning names right and left that I don't understand so I don't even know when I can pipe in without sounding ridiculous. On the other hand, it's rather nice to feel like a beginning student again and not responsible for knowing, if not everything, at least a little something!

This even I heard an amazing poet recite *her own* 30 minute poem aloud ... it was somehow about the flood in New Orleans and it blew me away. I can barely recite Emily Dickenson...

Saturday, July 07, 2007

Accessibility, Cliche and Carrion

"The artist: disciple, abundant, multiple, restless.

The true artist: capable, practicing, skillful;

maintains dialogue with his heart, meets things with his mind.

The true artist: draws out all from his heart,

works with delight, makes things with calm, with sagacity,

works like a true Toltec, composes his objects, works dexterously, invents;

arranges materials, adorns them, makes them adjust.

The carrion artist: works at random, sneers at the people,

makes things opaque, brushes across the surface of the face of things,

works without care, defrauds people, is a theif."

The lecturer said that for "carrion" we might read "post-modern." Ouch, but right on.

I also heard a fascinating lecture by Bruce Haxton on cliche. I'm currently muddling over the difference between cliche, dead metaphor and live metaphor. Haxton argued that cliche, though not perhaps the aim of poetry, works quite effectively occasionally and then because it can rely on a commonality between reader and writer. A completely novel metaphor has fewer such commonalities to moblize for its effect. A dead metaphor -- "the leg of a chair" or "the brook ran around the hill" -- seems to assume complete commonality of meaning between reader and writer: for both, "leg" and "run" transfer meaning (i.e. perform metaphorically) but in a complete way. In a novel metaphor, such as Yeat's "their throats were the throats of birds," the reader must perform many more (in fact, an infinite, incompletable series) of transformations on the terms to find the common meaning. A cliche seems to be somewhere in between these two ends.

Finally, I got really angry at a lecture on metaphor itself. The lecture was given by a well-known poet who presented a sort of big-picture historical (i.e. Neanderthals on) account of language development in relation to myth and metaphor. He concluded by appealing to Chompskian linguistics as evidence that language is hard-wired... and then somehow that myth was also hard-wired. (I am no expert in Chompsky, but I'm pretty sure he specifically separates cultural and linguistic practices. I tried to mention the Piruhua controversy, but he would have none of that) He also claimed that Kantian dualism was just like the left-brain right-brain split (which caused me to tear up some near-by paper), and that MRI scans can "without a doubt" prove that you are lying. (see a New Yorker article that pans exactly that assertion) It's not just the New Yorker but lots of conscientious cognitive scientists who'd admit that MRIs, while very cool, are not the final word on intentionality.

Although I had a personal distaste for the lecture because he was a stodgy old white man, I also had fear for the audience. This group of poets and writers took his word as gospel! The humanities bowed before the idol of the MRI. Instead of the poets and shamans having powers, it's the techies. Far from advocating a return to shamanism, I wish more humanities people (including myself!) were better educated to be able to assess these assertions without blindly sliding into scienticism. Perhaps a bit of scientism is a healthy for the humanities that can suffer equally from Romanticism, but it all has the air of mysticism... Yeats bought into automatic writing and they're looking at MRI scans, the latest phlogiston.

In any case, I certainly won't have to deal with that lecturer's brand of scientism any more because I offended him enough to ward of future conversations...

Now to bed and up early for more poetry boot camp...